3 марта 2019

The “Other Side” Is Not Dumb

There’s a fun game I like to play in a group of trusted friends called “Controversial Opinion.” The rules are simple: Don’t talk about what was shared during Controversial Opinion afterward and you aren’t allowed to “argue” — only to ask questions about why that person feels that way. Opinions can range from “I think James Bond movies are overrated” to “I think Donald Trump would make an excellent president.”

Usually, someone responds to an opinion with, “Oh my god! I had no idea you were one of those people!” Which is really another way of saying “I thought you were on my team!”

In psychology, the idea that everyone is like us is called the “false-consensus bias.” This bias often manifests itself when we see TV ratings (“Who the hell are all these people that watch NCIS?”) or in politics (“Everyone I know is for stricter gun control! Who are these backwards rubes that disagree?!”) or polls (“Who are these people voting for Ben Carson?”).

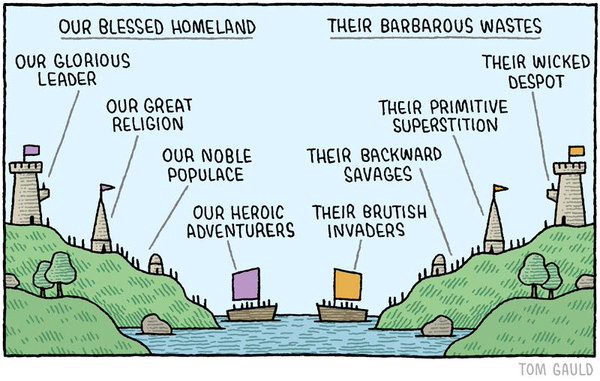

Online it means we can be blindsided by the opinions of our friends or, more broadly, America. Over time, this morphs into a subconscious belief that we and our friends are the sane ones and that there’s a crazy “Other Side” that must be laughed at — an Other Side that just doesn’t “get it,” and is clearly not as intelligent as “us.” But this holier-than-thou social media behavior is counterproductive, it’s self-aggrandizement at the cost of actual nuanced discourse and if we want to consider online discourse productive, we need to move past this.

What is emerging is the worst kind of echo chamber, one where those inside are increasingly convinced that everyone shares their world view, that their ranks are growing when they aren’t. It’s like clockwork: an event happens and then your social media circle is shocked when a non-social media peer group public reacts to news in an unexpected way. They then mock the Other Side for being “out of touch” or “dumb.”

Fredrik deBoer, one of my favorite writers around, touched on this in his Essay “Getting Past the Coalition of the Cool.” He writes:

[The Internet] encourages people to collapse any distinction between their work life, their social life, and their political life. “Hey, that person who tweets about the TV shows I like also dislikes injustice,” which over time becomes “I can identify an ally by the TV shows they like.” The fact that you can mine a Rihanna video for political content becomes, in that vague internety way, the sense that people who don’t see political content in Rihanna’s music aren’t on your side.

When someone communicates that they are not “on our side” our first reaction is to run away or dismiss them as stupid. To be sure, there are hateful, racist, people not worthy of the small amount of electricity it takes just one of your synapses to fire. I’m instead referencing those who actually believe in an opposing viewpoint of a complicated issue, and do so for genuine, considered reasons. Or at least, for reasons just as good as yours.

This is not a “political correctness” issue. It’s a fundamental rejection of the possibility to consider that the people who don’t feel the same way you do might be right. It’s a preference to see the Other Side as a cardboard cut out, and not the complicated individual human beings that they actually are.

What happens instead of genuine intellectual curiosity is the sharing of Slate or Daily Kos or Fox News or Red State links. Sites that exist almost solely to produce content to be shared so friends can pat each other on the back and mock the Other Side. Look at the Other Side! So dumb and unable to see this the way I do!

Sharing links that mock a caricature of the Other Side isn’t signaling that we’re somehow more informed. It signals that we’d rather be smug assholes than consider alternative views. It signals that we’d much rather show our friends that we’re like them, than try to understand those who are not.

It’s impossible to consider yourself a curious person and participate in social media in this way. We cannot consider ourselves “empathetic” only to turn around and belittle those who don’t agree with us.

On Twitter and Facebook this means we prioritize by sharing stuff that will garner approval of our peers over stuff that’s actually, you know, true. We share stuff that ignores wider realities, selectively shares information, or is just an outright falsehood. The misinformation is so rampant that the Washington Post stopped publishing its internet fact-checking column because people didn’t seem to care if stuff was true.

Where debunking an Internet fake once involved some research, it’s now often as simple as clicking around for an “about” or “disclaimer” page. And where a willingness to believe hoaxes once seemed to come from a place of honest ignorance or misunderstanding, that’s frequently no longer the case. Headlines like “Casey Anthony found dismembered in truck” go viral via old-fashioned schadenfreude — even hate.

…

Institutional distrust is so high right now, and cognitive bias so strong always, that the people who fall for hoax news stories are frequently only interested in consuming information that conforms with their views — even when it’s demonstrably fake.

The solution, as deBoer says, “You have to be willing to sacrifice your carefully curated social performance and be willing to work with people who are not like you.” In other words you have to recognize that the Other Side is made of actual people.

But I’d like to go a step further. We should all enter every issue with the very real possibility that we might be wrong this time.

Isn’t it possible that you, reader of Medium and Twitter power user, like me, suffer from this from time to time? Isn’t it possible that we’re not right about everything? That those who live in places not where you live, watch shows that you don’t watch, and read books that you don’t read, have opinions and belief systems just as valid as yours? That maybe you don’t see the entire picture?

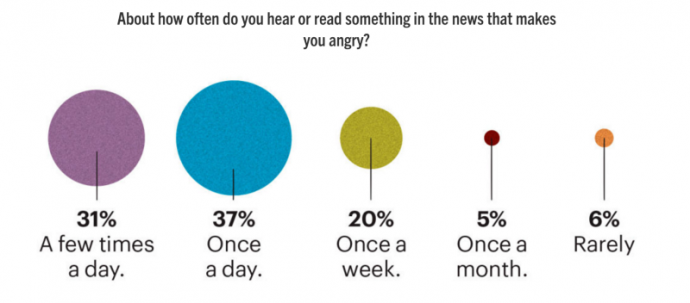

Think political correctness has gotten out of control? Follow the many great social activists on Twitter. Think America’s stance on guns is puzzling? Read the stories of the 31% of Americans that own a firearm. This is not to say the Other Side is “right” but that they likely have real reasons to feel that way. And only after understanding those reasons can a real discussion take place.

As any debate club veteran knows, if you can’t make your opponent’s point for them, you don’t truly grasp the issue. We can bemoan political gridlock and a divisive media all we want. But we won’t truly progress as individuals until we make an honest effort to understand those that are not like us. And you won’t convince anyone to feel the way you do if you don’t respect their position and opinions.

A dare for the next time you’re in discussion with someone you disagree with: Don’t try to “win.” Don’t try to “convince” anyone of your viewpoint. Don’t score points by mocking them to your peers. Instead try to “lose.” Hear them out. Ask them to convince you and mean it. No one is going to tell your environmentalist friends that you merely asked follow up questions after your brother made his pro-fracking case.

Or, the next time you feel compelled to share a link on social media about current events, ask yourself why you are doing it. Is it because that link brings to light information you hadn’t considered? Or does it confirm your world view, reminding your circle of intellectual teammates that you’re not on the Other Side?

I implore you to seek out your opposite. When you hear someone cite “facts” that don’t support your viewpoint don’t think “that can’t be true!” Instead consider, “Hm, maybe that person is right? I should look into this.”

Because refusing to truly understand those who disagree with you is intellectual laziness and worse, is usually worse than what you’re accusing the Other Side of doing.

[Thanks for reading! If you liked this, you’d love “The Discourse,” my newsletter about the intersection of tech, media, and politics. Subscribe here. Sent every other Thursday.]

The social network prioritizes “engagement” over enjoyment in video — hurting publishers and users alikeFrom the outside, it’s hard to know what, exactly, Facebook wants from its video platform. For years, the company told publishers that video was the future, even as it allegedly goosed statistics behind the scenes to make the format look more important than it was. In 2017, the social network rolled out a major update to its video player that added a kind of picture-in-picture mode to the News Feed, among other changes, in an effort to make “watching video on Facebook richer, more engaging and more flexible,” according to the company. Then last year, Mark Zuckerberg announced the company would de-prioritize video from brands in favor of content that “encourage[s] meaningful interactions.”The message seemed clear: Time spent watching video doesn’t matter to Facebook if people don’t also like, comment, and share those videos. In that statement, Zuckerberg referenced “connecting” or “interacting” with people nine times while disparaging what he called “passive” viewing twice. His model offers a curious contrast to most video platforms, which have been passive by nature since the Lumière brothers put on the first public screening of motion pictures in 1895. When you go to a movie theater, there’s nothing to engage with but the screen in front of you. (Keep that phone in your pocket, please.)Netflix has tried and failed to become more social, and its video player is still a sit-back experience, Bandersnatch notwithstanding. Even YouTube, notorious for its unruly comment sections, keeps most of its social features below the fold.So how can Facebook encourage “meaningful interaction” with content that seems meant to be viewed passively? The design of its video player offers a clue. Where most video platforms make the ritual of “Like, Share, and Subscribe” an optional step after you view a video, Facebook’s video player guides users to engage first.Consider this scenario: You’re scrolling through Facebook on your computer and find a video your friend has shared. You click on the video to start playing it. After watching a bit, you need to pause for a second. How would you do it? In players like Netflix, YouTube, and Vimeo, you can click anywhere on the video to pause. Facebook takes a different approach. Click on the video in your Facebook feed, and this will happen:The video enlarges and redirects to a page with a large “How People Reacted” section on the right side in addition to the usual comment section below. Prominent “Like,” “Comment,” and “Share” buttons appear directly below the video along with a tally of how many people have interacted with it.This new section leads to the original source of the video: If your friend shared a clip from LADbible’s page, for example, tapping the video brings you to that publication’s original post. You’re no longer in a feed populated by your Facebook friends but on a comments page filled with strangers. It’s hard to describe this as “meaningful,” to draw on Zuckerberg’s favorite word, but it is certainly an “interaction.”A similar thing happens if you attempt to full-screen a video from your feed. While most video players have a full-screen button — usually denoted with arrows or brackets indicating the corners of your screen — Facebook only has an “Enlarge” button with two arrows pointing to the corners. Click this, and you might expect the video to go full screen, but instead the same reaction occurs: You’ll be hit with a slightly larger video and much more prominent engagement buttons. Only then can you click another button to go truly full-screen, but Facebook doesn’t want you to forget that the option to engage is there — always.Even if you scroll on from a video in the News Feed, it’s difficult to disengage. On other scrollable platforms like Twitter or Facebook’s own Instagram, you can click on a video to play it, but scroll onwards and the video will go away. Not so on Facebook.Keep your eye on upper-right corner in the clip below:The video follows you as you scroll through your News Feed. And in the bottom right corner of that mini player are “Like” and “Share” buttons. These buttons take up more real estate inside the mini player than any other button (including the “X” in the top-right corner that dismisses the video).It’s hard to say whether this video player has been intentionally designed to funnel as many people into engaging as possible or if it’s just a clumsy interface. The company did not respond to multiple requests for comment.Whatever the case, the benefit to the company is clear. According to the company’s most recent earnings call, per-user revenue was up nearly 20 percent compared to the previous year, despite a scandal-filled 2018. Analysts credit, among other things, Facebook’s strong engagement trends.According to a study from social media manager Hootsuite in July 2018, videos on Facebook had a 6 percent engagement rate, which is a full 2 percent higher than the average rate for all other post types. Video was also the only post type to see an overall quarter-over-quarter increase in engagement.The more users engage, the more valuable they become. If a subtle, slightly annoying tweak to a video player leads to more shares and comments, Facebook can make more money, even if the user experience is worse.These changes leave Facebook video stuck, however, unable to fully please any of the groups that use it. Viewers can ignore video in their feed entirely, but if they accidentally tap a clip while they’re scrolling, they have to jump through hoops to perform basic functions like pausing or closing the video.Many publishers have meanwhile stopped making Facebook video a priority since the platform’s algorithms have changed. Advertisers have sued Facebook for misleading statistics about how well its platform is performing (though that hasn’t stopped them from spending). No one is totally happy.As Dan Olson, the YouTuber behind the media criticism channel Folding Ideas, explains, the experience has degraded for creators and users alike.“I experimented with uploading video directly to Facebook and it was terrible,” Olson tells OneZero. “The interface is bad, the guidelines are bad, the metrics are bad (and, as we know now, largely fabricated). So, I wouldn’t use it because it’s an awful system with negligible returns.”But for now, Facebook’s video player is the only viable option for sharing or watching video on the largest social platform in the world. It’s an obvious but serious point, given that 1.52 billion people reportedly log onto the site every day. Many of them will see videos in their News Feeds, and they will continue to feed the machine — however accidentally — that puts them there.

Показать полностью…

каждый из нас немного этот грузовичок