Medium

7 марта 2019

8 Productivity Strategies You Can Use To Take On The Most Hectic Days

There’s no such thing as a slow day when you’re an entrepreneur.

To me, the most anxiety-producing days are the ones where a lot of people need my time. These are days filled with a never-ending stream of meetings, calls, requests, and interactions — with little time to reflect in between. And when the work backlog keeps rising, and I don’t have a minute of “think time” to myself, it can be easy to start operating in a reactive (and not proactive) state.

I love people. I actually thrive when managing teams. But part of being successful is finding ways to remain calm and clear during hectic moments of the journey. When my days get crazy and difficult to manage, I use a series of productivity hacks, mental tricks, and other strategies to make sure I’m achieving progress, not simply motion.

Here are some of my favorite strategies for staying grounded and productive during a hectic day:

1. Block out time for everything, not just meetings.

Try putting everything you need to accomplish on your calendar. For example, I might block off ninety minutes to develop a plan for a makeup testing panel (my startup, NakedPoppy, is a clean beauty company), or an hour to work on recruiting. Blocking time also prevents me from spending more time than I think the task is worth — when the time is up, it’s time to stop.

I even block off time on my calendar to think.

I set aside “think time” at least three times a week. “Think time” means no phone, no peeking at Slack, and no checking emails — just deep thinking and concentration. I learned this “deep thinking” approach from Victoria Treyger, a wonderfully successful former executive turned venture capitalist.

2. Do one thing at a time. Period.

When you’re extremely busy, there’s the temptation to multitask.

Have you ever had that moment when two people are texting you, someone is sending you Slack messages, and someone else is trying to get you on the phone? When it happens to me, my initial impulse is to jump from one to the other and answer everyone as quickly as possible.

But I try to fight that instinct and instead focus on each conversation to give it the attention it deserves. For example, if I’m on a call, I try to be 100% present. That means no texting or looking at email.

When you multitask, you end up with two (or more!) suboptimal results. Give all your attention to a single interaction at a time, and the outcome will be better.

3. Start each week by writing down 1–3 actions that will move the needle on your business.

At the beginning of each week, I write down the top three actions — in priority order — that I need to take to move the business forward. I revisit them daily to keep my focus.

The work that matters most is rarely the quickest or easiest. It could be recruiting key talent, launching a new initiative, or raising money.

It’s easy for these larger efforts to get pushed to the next day, and the day after that, and so on. So I make sure that the first thing I’m thinking about each morning is one of my top priorities.

4. Scan your calendar in advance. Optimize when needed.

Don’t let another person, no matter how trusted, take full control of your time. It’s YOUR time. Scan your calendar in advance and re-calibrate if needed.

For example, maybe there’s a non-urgent meeting that requires a level of thoughtfulness you can’t summon on a crazy day. Reschedule the meeting. The key is to do the rescheduling well in advance. That’s far more gracious than running late, being distracted, or postponing at the last minute.

5. Resist the temptation to put off certain internal meetings.

This might sound like it contradicts the previous point. But try and resist the temptation to delay internal meetings when team members need your input in order to move forward.

I want my team to feel happy and valued, which in itself advances the business. And they often just need a quick clarification to be more focused and productive.

Even on the craziest days, remember that your leverage comes from your team. Help them be more productive, and you’ll amplify your accomplishments.

6. Set your perspective at the beginning of each day.

This matters.

If you start your day with a mentality of, “I have way too much to do today!” you’re setting yourself up to feel overwhelmed.

To counter this, I say to myself, “I have plenty of time to do what needs to be done today.” This mindset helps me open up my body and mind to accomplish what matters most. I can then take a deep breath to prioritize, break tasks down into manageable chunks, and block off the calendar time to get them done.

7. Never skip self-care.

When you’re stressed out, it’s easy to skip the things that keep you sane. But don’t forget that the success of your business or career is closely tied to your wellbeing.

My co-founder, Kimberly Shenk, is a marathon runner, and she taught me to think of exercise as a meeting that cannot be rescheduled. My morning routine is to come down the stairs and exercise before I have the chance to tell myself, “Maybe not today.”

I treat meditation the same way. If it’s a crazy day, and my mind is really racing, I tell myself that meditating for even three minutes is better than not doing it at all. And if you don’t have three minutes, you don’t have a life.

Finally, I never shortchange myself when it comes to sleep. I get my eight hours. For me, productivity depends on feeling rested. I’m fortunate to have few physical distractions during the day — no pain, sleepiness, or brain fog — and believe that for me it’s the result of prioritizing sleep, meditation, and exercise.

8. Don’t forget to enjoy it.

When I’m at my most overwhelmed, I remind myself that I’m lucky.

I’m co-founder and CEO of a company I love, which is a passion project as well as a business. What a privilege it is that I have this busy, exciting day, surrounded by people I enjoy.

When I start to feel overwhelmed, my favorite way to ground myself is to remind myself that it’s a marathon and not a sprint. Make sure you have a set of tools (I hope some of my suggestions will help you!) to give you the mental and physical fortitude to succeed.

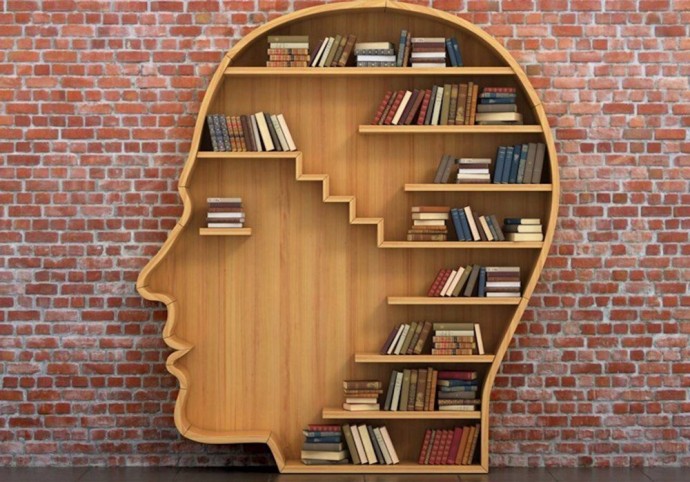

If You Only Read A Few Books In 2018, Read These

If you’d liked to be jerked around less, provoked less, and more productive and inwardly focused, where should you start?

To me, the answer is obvious: by turning to wisdom. Below is a list of 21 books that will help lead you to a better, stronger 2018.

Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World by Cal Newport Media consumption went way up in 2017. For most of us, that meant happiness and productivity went way down. The world is becoming noisier and will become more so every day. If you can’t cultivate the ability to have quiet, insightful, deeply focused periods of productive work, you’re going to get screwed. This is a book that explains how to cultivate and protect that skill — the ability to do deep work. I strongly urge you to begin this practice in 2018— if you want to get anything done or perform your best.

The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good Life by Mark Manson To me, practical philosophy has always been the art knowing what to — and what not to — give a fuck about. That’s what Mark’s book is about. It’s not about apathy. It’s about cultivating indifference to things that don’t matter. Be careful, as Marcus Aurelius warns, not to give the little things more time and thought they deserved. Maybe looking back at this year reveals how much effort you’ve frittered away worrying about the trivial. If so, let 2018 be a year that you only devote energy to things that truly matter — get the important things right by ignoring the insignificant.

The Way to Love: The Last Meditations of Anthony de Mello by Anthony de Mello Coach Shaka Smart recommended this little book (and it’s a little book, probably the smallest I’ve ever read. It fits in your palm). But it’s an incredibly wise and helpful read. Written by a Catholic Priest who’d lived in India, the book has this unusual convergence of eastern and western thought. One of my favorite lines: “The question to ask is not ‘What’s wrong with this person?’ but ‘What does this irritation tell me about myself?’ I plan on regularly revisiting it throughout 2018.

But What If We’re Wrong by Chuck Klosterman It’s always good to remind ourselves that almost everything we’re certain about will probably be eventually proven wrong. Klosterman’s subtitle — Thinking About the Present As If It Were the Past — is a brilliant exercise for getting some perspective in 2018. Whether you think it’s going to be a year of radical change for the better or a horrible year of excesses of dangerous precedent, you’re probably wrong. You’re probably not even in the ballpark. This book shows you why, not with lectures about politics, but with a bunch of awesome thought experiments about music, books, movies and science.

Rules for Radicals: A Practical Primer for Realistic Radicals by Saul Alinsky If Hillary Clinton had remembered the lessons of Saul Alinsky (who she wrote her college thesis on), the election may have turned out differently. Why? A notorious strategist and community organizer, Alinsky was a die hard pragmatist, but he also knew how to tell a story and create a collective cause. He could work within the system but knew how to shake it up and generate attention. This book is a classic and woefully underrated. Whatever you set out to do in 2018, this book can provide you with strategic guidance and insight.

The Filter Bubble by Eli Pariser / Trust Me I’m Lying by Ryan Holiday / The Brass Check by Upton Sinclair I strongly recommend that you take the time in 2018 to read these books. In light of this year, you owe it to yourself to study and better understand how our media system works. In The Filter Bubble, Eli Pariser warns of the danger of living in bubbles of personalization that reinforce and insulate our worldview. Though Sinclair’s The Brass Check has been almost entirely forgotten by history, it’s not only fascinating but a timeless perspective. Sinclair deeply understood the economic incentives of early 20th century journalism and thus could predict and analyze the manipulative effect it had on The Truth. I used that book as a model for my expose of the media system, Trust Me, I’m Lying. Today, the incentives and pressures are different but they warp our information in a similar way. In almost every substantial charge Upton leveled against the yellow press, you could, today, sub in blogs and the cable news cycle and be even more correct.

48 Laws of Power / 33 Strategies of War by Robert Greene Robert Greene is a master of human psychology and human dynamics — he has a profound ability to explain timeless truths through story and example. You can read the classics and not always understand the lessons. But if you read Robert’s books, I promise you will leave not just with actionable lessons but an indelible sense of what to do in many trying and confusing situations. I wrote earlier this year that strategic wisdom is not something we are born with — but the lessons are there for us to pick up. Pick these two up before the year ends and operate the next with a strategic mindset and clarity.

Conspiracy: Peter Thiel, Hulk Hogan, Gawker, and the Anatomy of Intrigue by Ryan Holiday — If you want to immerse yourself in the above topics of media and strategy, and are looking for one book to teach you lessons in both, my book on the nearly decade-long conspiracy that billionaire Peter Thiel waged against Gawker will do this for you. This is a stunning story about how power works in the modern age, and is a masterclass in strategy and how to accomplish wildly ambitious aims.

The Road To Character by David Brooks When General Stanley McChrystal was asked on the Tim Ferriss podcastwhat was a recent purchase that had most positively impacted his life, he pointed to this book. I agree. It can be a bit stilted and dense at times, but it should be assigned reading to any young person today (a little challenge is a good thing). Illustrating with examples and stories from great men and women, Brooks admonishes the reader to undertake their own journey of character perfection. In my own book, I explore the same topic (humility) from a different angle using similar stories — I’m attacking ego, he’s building up character. Both will be important for the next year.

The Dip by Seth Godin This book is a short 70 pages and it looks like something someone would give as a joke gift, but it’s anything but. Godin talks frankly about quitting and pushing through — and when to do each. Quit when you’ll be mediocre, when the returns aren’t worth the investment, when you no longer think you’ll enjoy the ends. Stick when the dip is the obstacle that creates scarcity, when you’re simply bridging the gap between beginner’s luck and mastery. I promise, next year you are guaranteed to find yourself in moments when you don’t know what is the right answer. This book will help you find it.

Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis by J. D. Vance / Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right by Arlie Russell Hochschild You might describe Hillbilly Elegy as a Ta-Nehisi Coates style memoir about a community that — at least in progressive circles — gets a lot less attention: disaffected, impoverished whites (particularly in the mid-east and South). I thought the book was empathetic, self-aware and inspiring. The author pokes some holes in the concept of “white privilege” — certainly a third or fourth generation hillbilly in Kentucky doesn’t walk around feeling like they have it easy — and an explanation of some of the phenomenon behind Donald Trump (notice I said explanation, not an excuse). This is a sober but also hopeful book. I urge people on all sides of the political spectrum to read it, but progressives would benefit from the eye-opening perspective the most. Pair it with Strangers in Their Own Land, the author of which, a Berkeley native, visits and interviews people in the deep Louisiana countryside. (Remember: you don’t have to agree with the people you’re reading about — but you should care what makes them tick.)

It Can’t Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis This book is one that will make you so uncomfortable that you’ll probably pick it up and put it down several times. It almost shocks you that this exists, that it’s not some work of fiction pretending to be 80 years old. But no, in fact, one of America’s most famous writers wrote a bestselling book about an appalling populist demagogue who won the presidency of the United States. Europe was a mess, the economy was in the toilet. Well meaning people talked earnestly about the need for “serious change” and “revolution.” The parties split, and a fringe candidate suddenly becomes viable. When people tried to question some of the ideas he campaigned on, they were shouted down: “This is how all politicians speak. He’s not serious about that extreme stuff.” Life imitates art and now, this is what actually happened. Change the dates, places and names and it’s no longer fiction, it’s real. Fiction is best when it puts a mirror up to us. This book does that. If you don’t read the book, at least please read about it. Because you need to know. It can happen here.

How to Live: Or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer by Sarah Bakewell The book is spectacular. It was a bestseller in the UK and was featured in a 6 part series in The Guardian. The format of the book is a bit unusual, instead of chapters it is made up of 20 Montaigne style essays that discuss the man from a variety of different perspectives. Montaigne was a man obsessed with figuring himself out — why he thought the way he did, how he could find happiness, his fetishes, his near-death experiences. He lived in tumultuous times too and he coped by looking inward. We’re lucky he did, and we can do the same.

Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging by Sebastian Junger Junger looks at many of the social issues we have today: PTSD. Depression. Political polarization. Contempt for our fellow citizens. Aimlessness. We’ve lost the bonds that tie a tribe and culture together. No wonder veterans feel alone and lost when they leave their tight knit tribe and re-enter solitary civilian life. No wonder manypeople feel that way regardless of whether they served or not. No wonder we have trouble agreeing on basic solutions to common problems. There is no sense of what is common or basic or shared. Given the divisiveness that we are facing as a society — that became painfully clear in 2016 — this is one of the most urgent and important book you need to read next year.

The Years of Lyndon Johnson (4 Volumes) by Robert A. Caro In January of 2016, I picked up my first book in this Caro’s series on Lyndon Johnson. It wasn’t until June that I finished my fourth, but I consider finishing all (~3,500 pages) of them to be one of my proudest reading achievements. If there is one line that sums up the whole series it’s this: It’s that power doesn’t only corrupt. That’s too simple. What power does is reveal. It’s also easy to be disillusioned by politics right now but for me, getting lost in these Lyndon Johnson books has been a helpful and educational process. Because you learn two things 1) that things have always been complicated and confusing but they tend to turn out alright 2) that our system, whatever its flaws, can still produce good results from bad men. And without a doubt, that’s a good reminder to have on the eve of 2018.

The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill (3 Volumes) by William Manchester Don’t think an individual can make a difference in history? Then you haven’t read enough about Winston Churchill. The scenes in this book: warning about the looming threat of Nazism, the retreat at Dunkirk, persevering through the Blitz, vowing to fight on the landing grounds and the beaches and in the streets, whatever the cost may be. The sheer determination of this man, to take an entire country on your back and defy a horde which had overrun the European continent in a matter of months…it’s almost breathtaking to think about. (If you were to only read one thing in the next year, you could do a lot worse than either of these series. They contain dozens of books within them and will teach you about so much more than just the man they are ostensibly about. Please, please read them.)

Mr. Eternity by Aaron Thier / The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas These books really have nothing to do with the events of 2016 but they are long and entertaining and they will make you forget your problems for the next 12 months. I thought I’d read Monte Cristo as a kid, but clearly I didn’t. Because the actual book is a 1,200 page epic of some of the most brilliant, beautiful and complicated storytelling ever put to paper. What a book! When I typed out my notes (and quotes) after finishing this book, it ran some 3,000 words. As for Mr. Eternity, it’s a fun, epic jaunt through the distant future (as though it was the past) in the vein of Voltaire’s Candide. Candide isn’t a bad read for this year either: “We must cultivate our own garden.”

Like to Read?

I’ve created a list of 15 books you’ve never heard of that will alter your worldview and help you excel at your career.

What’s wrong with MMT?

Recently there have been many articles criticising Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), but there seems to be near universal agreement from MMT economists that these articles are attacking a strawman version of MMT, and that their true views are misrepresented — and this may be true. One difficulty in critiquing MMT is that there seems to be slightly different versions of MMT floating around online: MMT as exists in obscurer academic literature, including some older Post-Keynesian literature; MMT as it exists among various economics bloggers; and MMT as it exists on social media and on comments sections. In this article I will attempt (but probably fail) to critique MMT in good faith, but I will be targeting MMT as it is generally presented to the public — that is where I’ve digested most MMT content: mainly through MMT bloggers and on twitter. If this is at odds with some more academically pure version of MMT that exists in the literature, I can only suggest that modern monetary theorists could then work on their messaging somewhat. Perhaps the best way to start a good faith critique of MMT is to list its strong points of MMT:

The Good

· A positive vision. So much so called ‘heterodox’ economic literature simply consists of criticism of existing economic models and policies (which is easy to do — they are generalised simplifications by design), without offering an alternative framework or set of policy prescriptions. MMT on the other hand is a positive movement, in the sense that it doesn’t just critique orthodoxy but provides a new macroeconomic framework and a set of policy prescriptions that offer a positive vision for the future for progressives and centrists alike without the baggage and militant history associated with previous left wing movements. One might effectively argue that this mix of positive economic analysis and political activism is inherently compromising, but it is refreshing nonetheless.

· Politically effective. While this is by no means exclusive to them, MMT economists are effective at countering claims from austerians and hard money types and have reinforced important concepts from traditional macro like the aggregation fallacy of treating an entire economy and government budget like a single household that’s insulated from feedback effects. Furthermore, it is certainly true that for some countries, obsessing over how to pay for new investment and transformative policies can get you really stuck in a rut. Modern monetary theorists (MMTists) are right that for really important measures it’s often better to simply spend and invest the money now and figure out how to get funding later — they will point out for instance that nobody asked how we were meant to pay for a very costly and wasteful war in Iraq and yet that didn’t result in a budget crisis, so why should we obsess over it for important policies like tackling climate change? This resonates with me, things like government debt and interest rates are just numbers on a spreadsheet — in times of crisis we shouldn’t worry about spreadsheets holding us back, it’s the real resources we have available that matters.

· Not zero sum. So many previous progressive movements have been inherently austere by nature; demanding we reign in excess consumerism — or even going full Neo-Malthusian and insisting we embark on ‘degrowth’ and simply redistribute existing wealth to compensate. True to Keynes, and honestly modern economics in general, MMTists recognize that the idea that prosperity and social progress must compromise with growing the economy is a fallacy.

· Renewed interest in institutional detail. Again, while this is definitely not exclusive to MMTists , a lot of content has been produced by MMT economists detailing the monetary operations and institutional structure of ‘monetarily sovereign’ governments , much of it useful and illuminating — showing that some existing economic models contain implicit assumptions about monetary operations that may be wrong. Details such as these used to be dismissed as trivial or ‘netted out’ by some economists when in fact they can matter a lot, and it’s great to see renewed interest in methodically detailing how our economic institutions actually work in practice. However, I happen to think that MMT makes many wrong or dubious claims about the modern monetary systems and their operations too, which leads nicely onto the next section:

The Bad : Monetary crankery

MMTists often like to position themselves as the only ones to properly understand the ‘operational realities’ of modern monetary systems. Ironically, many of the claims made by MMTists on this topic are misleading at best. One common rhetorical tactic that I’ve noticed they employ, which often catches their critics out, is to use the term ‘government’ in a way that’s different typically from how it is used in mainstream economics. When they say ‘government’, they tend to include basically any institution that is an agent of the state, including the central bank — hence the ‘government’ here includes consolidating the treasury and the central bank into one entity, effectively ignoring or assuming away any independence the central bank may have.

This allows them to make assertions such as that money is created by government spending, or for instance, as Kelton claims, that government spending is “self-financing”. What’s even more confusing is that some supporters will often use the ‘treasury’ and ‘government’ interchangeably, despite the terms meaning very different things, and then essentially claim that even the treasury creates money when spending, which is definitely false, which I’ll get to later.

From these premise they are able to make further dubious semantic claims, such as that taxes and borrowing don’t actually “fund” government spending at all, and that the true purpose of taxation is to remove excess high powered money from the economy — in other words, taxes and borrowing are monetary policy operations. What’s interesting about this claim, I argue, is that it’s doubly wrong: it’s wrong both in a nominal operational sense and it’s wrong in a ‘real’ resource sense.

In a nominal sense, nominal funding simply means acquiring money before spending it. A general economic rule I propose is that for money users in a modern banking system, all credits require debits; the only entity that can credit without debiting is the one authorised to issue the money. What about the government? Since it can issue money, does this maxim still apply to it? Does the government need to nominally fund its expenditure still? Well, yes, in practice. Expenditure is carried out by the treasury, so let’s start there: typically the treasury is not authorised to issue the most common form of high powered money that is actually used for spending — bank reserves, and I believe in MMTists will agree with me so far. Thus in practice, the treasury has to secure this money in order to spend it, which it does by debiting its account at the central bank in order to credit other accounts. Technically, the treasury can issue physical currency, but government spending is practically never done this way in modern democracies (not that their haven’t been attempts, such as the ill fated mint the coin proposal).

Another important point is that the treasury cannot typically overdraw from its account at the central bank. In the United States JP Koning notes that it is currently illegal for the treasury to have an overdraft with the Federal Reserve. Thus, the treasury can only spend by first ensuring it has adequate funds in its account with the central bank. How does it do this? By collecting taxes receipts and selling bonds. Thus, taxing and borrowing does indeed fund treasury spending specifically. But what about the government in general? This is where the semantic headaches start; as stated earlier, typically in mainstream discourse when we talk about “government spending” we’re talking about spending from the treasury, not a consolidated treasury — central bank entity, which causes some of the confusion in the first place. But let’s define government in this way, for the sake of argument — does it then make sense to say that taxes/borrowing funds spending? After-all, this money is ultimately created by the government (the central bank) in the first place; it didn’t need taxes or borrowing to come into existence.

The answer is again: yes in practice. Whether MMTists want to admit it or not, while the central bank is an agent of the government (normally at least), it does still operate independently. When the government wishes to spend, it cannot simply demand funding from the central bank directly or even indirectly — it has to engage in borrowing and taxation without assuming any particular quantity of bonds will be purchased by the central bank. What MMTists will say here is that treasury and central bank will ‘coordinate’, setting up bond auctions and targeting a particular interest rate, with the CB purchasing bonds from the secondary market and expanding the money supply as needed, such that the treasury will always get the funding it needs. From here, they make the most bizarre claim in my opinion, which enables them to maintain the ‘taxes/borrowing not funding spending’ claim — they argue that the purpose of taxes and borrowing during this sequence of events is merely to ‘drain reserves’ from the system.

In other words, they claim, the purpose of taxation and borrowing is simply to remove the build-up of excess money from the economy that can occur when acquiring credit from the central bank, in order to maintain an interest rate target, or ultimately to stop inflation. To me this is manifestly absurd. To start with, intentions matter, if you ask any politician for what purpose they will approve any tax levied, I am confident exactly none of them will claim it’s in order to control the amount of reserves in the system as an anti-inflation measure (but I’m happy to be proven wrong). A more formal way that MMTists might put it is that taxes/net borrowing are simply a residual automatically adjusted to keep aggregate reserves in balance while the government acquires central bank credit to spend. The reality, of course, is that the central bank is the agency tasked with controlling the money supply, and will add or remove reserves via open market operations in order to target a particular interest rate, and hence it is commonly understood that it is central bank operations that act as the residual in controlling reserve balances, not taxing/borrowing.

As stated previously, central banks typically, including the federal reserve, are not legally allowed to directly finance the government, thus even if the government issues the money to begin with, as this money is issued by a separate independent agency to the agency that spends money (the treasury), the government must reclaim this money through taxes and borrowing before it can spend, which most people would regard as funding. So why do MMTists claim otherwise? The above linked Levy Institute paper dismisses such legal obstacles as “self imposed constraints”, but this is a red herring. Ultimately all economic institutions are largely composed of ‘self imposed constraints’, and it is by these constraints that we define how our economic institutions govern. One cannot assume away these constraints, assuming away the constraint that holds that spending must be tax and bond financed is in effect assuming the conclusion.

Additionally, in previous discussions I often see people try and substantiate these position by bringing up the ‘Treasury Tax & Loan Service’ (TTL), which is a system of distributing tax receipts across various select banks in the US banking sector as a buffer — they’ll point to how this system operates, whereby reserves are drawn from the TTL as needed when spending occurs, or otherwise, in order to ensure aggregate reserves remain in balance. But this is a highly obtuse argument: the TTLs are really just an internal mechanism employed by Fed to help with financial stability; when the Fed draws from these funds, this is not “taxation” in any meaningful sense — this money is already the government’s to begin with, as far as the public is concerned they were already taxed long ago. TTL operations should instead be considered a monetary policy operation, not taxation, and if an MMTist uses the TTL to argue that taxation is a monetary policy operation, you should consider this a fallacious rhetorical trick.

Now that we’ve hopefully established, in a long winded way, that government spending is in fact nominally funded by taxes and borrowing, we should move onto “real” funding. By this I mean providing the real resources necessary to purchase or deploy real goods and services. Both MMT and most of the mainstream essentially agree that governments have finite fiscal space — that is the ability to utilize idle resources to achieve its goals without competing with and bidding up already utilized resources. Here again many MMTists tend to argue then that government spending is simply the process of acquiring and utilizing resources — and that the purpose of taxation/borrowing is for when the government is close to an idle resource constraint but needs more resources. To claim that taxation or borrowing here should not be considered funding is again manifestly absurd. It is quite clear that in a real sense, a government’s “funds” is its fiscal space (defined as idle resources in real terms), and the only way to acquire more fiscal space than is already available, without reducing its own outlays, is to take it from others, in other words either by taxing them or borrowing from them — ergo in real terms taxing and borrowing unequivocally funds the government.

Monetary independence matters

Putting aside the question of whether the central bank really has any independence (MMTists will range from saying the idea of independence is a ‘sham’ to acknowledgement that the central bank at least has independence in ‘day-to-day’ operations), the question of how independent monetary policy decision making should be remains. To properly enact MMT policies, such as permanent zero interest rate policy, we could not have central bank independence (CBI), but most economists agree that at least some degree of CBI is very important. The reasons are fairly straightforward.

Some people argue that central bank independence is essentially a conspiracy to sabotage a progressive agenda and ensure money creation is unaccountable. But this is false, there are reasons why a degree of independence is desirable other than sinister ulterior motives, and independence does not imply non accountability: central bankers are still politically appointed, and have to adhere to a mandate set by politicians, which could change at any time. For a modern economy to properly function the currency needs to retain predictable value, if the value collapses or suffers extreme fluctuations then profound economic disruption and ruin can result. Both MMTists and the mainstream take inflation seriously as a problem. Most MMTists will tend to view inflation in a mechanical perspective: inflation occurs when demand (usually stimulated by government spending) is pushed beyond its resource constraint — while MMTists typically avoid models, this can essentially be reverse engineered to the economy having an L shaped AS curve in a typical AS-AD model — a standard Keynesian view and not particularly distinct from the mainstream. So far so good, but what does this have to do with CBI? What’s missing from this analysis so far is waste and credibility:

· Moral Hazard. Economists argue that the less independent monetary policy is, the more wasteful and non-credible economic policy can become. The most immediate cause under no CBI is moral hazard and conflicts of interest. If politicians can easily create money at will to fund any program they wish, such a responsibility may conflict with their responsibility (which they would have under scenarios where CBI is abolished) to ensure the currency doesn’t depreciate too much. Given that it can take a long time for inflation to occur, while the political payoffs from funding popular projects or tax cuts can be immediate, you have a classic moral hazard problem. When highly profligate spending and money creation does eventually cause inflation, it’s difficult to point to any particular project or tax cut as being a cause, hence an individual policymaker will tend to be shielded from the costs but gain privately from the individual projects they championed — this then approaches a tragedy of the commons problem.

· Soft Budget Constraints. But government investment isn’t necessarily inflationary if it increases productive capacity, could politicians theoretically just ensure all their spending is highly efficient? To make this claim, one would again, I argue, have to ignore modern economics — particularly the ground-breaking work by Janos Kornai on the “soft budget constraint” syndrome. Kornai observed this problem occurring particularly in highly planned economies such as in the Soviet Union — the simplest way to describe the problem is to note that the easier it is for a firm to acquire funding on demand, the less incentive they have to ensure their production is efficient, and the more incentive they have to engage in rent seeking. A clear moral hazard occurs when firms can be assured that the state will offer subsidies and financial assistance when needed. What MMT effectively does is make the government’s budget constraint as “soft” as possible — if a department, state firm or contractor knows that the politician they’re bargaining with for funds and pricing has effectively infinite funds, they can then “rip off” the government as much as possible, knowing full well that any claims, such as them having a limited budget or not having the cash available, would be a lie. The soft budget constraint syndrome will tend to cause ever rising costs, waste, inefficiencies and hence inflation.

Even before this happens, for smaller or less developed nations the public might fear that this might happen in the future, and hence avoid holding cash for fear of future inflation. If too many people have this same fear and dump the currency at the same time, the currency will depreciate straight away in what’s known as a self-fulfilling crisis. This is why economists take credibility seriously. If policymakers are in conflict with the central bank and are pushing through its abolition, this might signal to markets that the country is about to enter “tinpot” territory and cause participants to dump the currency, especially if enough of them believe that such a situation could result in the problems detailed in the above to paragraphs. This is what I call “psychological inflation”, it’s hard to impossible to predict the psychological response will be to economic policy — but it does matter, so governments should try to seem credible.

The purpose of monetary independence then is to avoid the moral hazard and ‘soft budget constraint syndrome’ issues that can arise when policy makers can both create and spend money at will. Entrusting a politically appointed separate agency with the task of adjusting the money supply and cost of borrowing ensures the conflict of interest described previously does not occur, and helps reassure economic participants that economic policy is credible and hence the currency safe. For what it’s worth, some MMTists appear to recognize the importance of separating responsibilities at least, such as Kelton who proposed separate agencies to evaluate new projects and ‘score inflation risk’ — but as I argued previously, it can take a while for inflation to materialize, and given that money is fungible it can be difficult to impossible to blame any specific government project on inflation. MMTists would need to demonstrate how such an agency would be superior to an agency that decides on the amount or cost of acquiring money (central bank) — and to date I have not seen fleshed out details on this hypothesised agency that could explain this. It would also need to resolve the problems associated with fiscal dominance, which I will go into further in the next section.

The theories behind abolishing CBI threatening monetary stability have empirical support too. There are many studies that attempt to construct an index of “central bank independence”, and use the values to predict the performance of various economic indicators such as inflation or growth. Two recent meta-analysis found the effect of CBI on inflation significant: Klomp, De Haan (2010) and Iwasaki (2017). Graphs such are these are common to show the relationship:

Is fiscal dominance stable?

In addition to opposing central bank independence, MMTists, like traditional Keynesians, are in general not too fond of using monetary policy to “fine tune” the economy in general. But MMTists go a step further in advocating that monetary policy in effect be permanently neutered, advocating for interest rates to remain permanently pegged at or near 0% (permanent zero interest rate policy: PZIRP) — in such a scenario this typically means the fiscal authorities are the ones responsible for controlling inflation, in the economics literature this is known as ‘fiscal dominance’.

One common criticism of high government deficits is to point to the build-up of debt that results. Economists usually respond by arguing that this doesn’t matter too much when interest rates are low. In economics, government debt is considered unsustainable when the interest paid on debt (‘r’) exceeds economic growth (‘g’): r > g. PZIRP is an attempt to deal with this potential problem by suppressing r permanently, and it has been observed that countries with very high debt levels will tend to be forced to adopt this policy. Given the higher deficits favoured by MMTists, it becomes more likely that we may be forced to adopt PZIRP too whether we want to or not. But is permanently suppressing rates, whether forced to or otherwise, a desirable situation? Economists argue that PZIRP (which can lead to financial repression) causes financial instability and that fiscal policy is ill suited to deal with inflation.

Post Keynesian economist Thomas Palley argues convincingly that setting rates to zero permanently would eventually force nominal appreciation of the dollar due to the covered interest parity — which would be in conflict with the money financed deficits and inflation associated with MMT’s full employment policy — which in turn would lead to financial instability. He notes that MMTists respond to this concern by advocating for exchange rate pegging — but such a peg would constrain the amount of new money that could be issued and would force foreign reserve holdings — this would effectively make the government less ‘sovereign’ in its money supply and undermine the core premise of MMT by introducing financial constraints on the government. He also cites other work from Aspromourgos showing that zero nominal rates can encourage financial speculation and asset price inflation, leading to financial crisis. There’s no guarantees, but one can’t deny the risks associated with PZIRP, so it does not seem to be a desirable policy in terms of financial stability.

The second issue is whether fiscal policy is an adequate way to control inflation — or more specifically: in this new scenario, under PZIRP, with no CBI, where the money supply is effectively expanded at will by politicians as needed for new spending, if or when inflation occurs will these same politicians be able to deal with it? There are several obvious issues that can arise here. As explored in the previous section — inflation policy becomes politically compromised; even under a situation of high inflation, fiscal policies required to deal with it — tax hikes, austerity — will still be highly unpopular, individual politicians may forego approving such measures in order to not upset their constituents. Passing legislation to deal with inflation and securing the votes needed then becomes very difficult and an undoubtedly slow and tedious process — for smaller counties this can be a recipe ripe for international speculators to attack the currency in the meantime. The core idea expressed by MMTists then, that fiscal authorities should continue to increase spending on social projects until we hit the ‘resource constraint’ (until inflation begins to spike), does not seem so straightforward after-all. The Job Guarantee is their method of ensuring, at least, that austerity does not lead to mass unemployment — putting aside whether this is politically feasible, and the political economy problems noted by Palley in the paper above — the guarantee of a minimum wage job would be little solace to most voters affected by austerity, so I cannot see how this would alleviate the above issues.

Studies, such as De Resende, Carlos

Rebei, Nooman (2008), find that countries with high degrees of fiscal dominance are associated with higher inflation, more severe business cycles and overall suffer significant welfare losses. MMTists often point to Japan as a counter-example, which effectively is constrained to PZIRP due to high debt levels, but still seems to be performing fine. I’m not sure this is an effective argument however: to start with, Japan has in fact suffered considerably over the last three decades — the lost decade saw serious stagnation and real wage decline. I’m not blaming this on fiscal dominance, my point here is that this, combined with the 2008 recession and demographic trends, acts as a strong deflationary countermeasure, reducing aggregate demand over decades which would surely have resulted in a large build-up of spare capacity. As such Japan has not yet had to grapple with inflation for a very long time, and ‘Abeonomics’ has much room to continue to stimulate the economy before inflation might arise. But if or when Japan does finally run out of spare capacity, and inflation becomes a threat, it’s not clear how effectively this will be dealt with. Given that Japan must import a considerable amount of energy, exchange rates are especially important, which might further complicate future anti-inflation policy by limiting the amount the currency can tolerably depreciate — as such one can’t yet consider Japan a true test of fiscal dominance, as we have not yet seen how it might react to an inflation problem.

Can countries avoid a fiscal dominance situation if the central bank or government owns much of its own debt? This is the argument Bill Mitchell implicitly tried to make towards the end of this article, arguing that we shouldn’t consider debt held by the BOJ as part of its debt burden, and hence Japan’s true debt ratio drops to 45%. But this may not stack up when considering fiscal dominance. To clarify, PZIRP is needed when the interest servicing costs to government from higher rates becomes too large a portion of government spending, or as Bill Mitchell puts it, takes up too much “fiscal space”. Does the government owning or monetizing the debt reduce this interest burden? Probably not, some like Ricardo Reis, argue that the scope for the central bank to lower the fiscal burden of debt is limited. Further, if a central bank buys up all or much of the debt, and the banking sector’s government bond holdings are replaced with excess reserves, this would have little effect on the interest burden — as to ensure a higher interest target is met, the same interest rate must be paid on excess reserves to act as the necessary price floor in the first place. In effect, replacing debt with central bank reserves is just replacing one liability with another — in terms of whether PZIRP is necessitated, it would make no difference.

Final thoughts, meeting half way?

The development of frameworks like MMT is understandable given the sway austerians and hard money enthusiasts have had over the media — but that does not excuse sloppy economics. Could there be a version of ‘MMT’ that achieves a progressive expansionary policy agenda without relying on dubious economic theory? I believe there a few things MMTists could do to start with:

First they should simply drop the confusing and misleading claims about whether taxes and borrowing fund government spending (framed as describing ‘operational realities’) — at best it’s speaking another language and stifling efforts to get other economists on board with the framework through semantic confusion, at worst it is simply flat out wrong.

Second, they should take more seriously the moral hazard issues associated with abolishing central bank independence and should consider instead allowing the central bank or another independent agency to control the amount of seigniorage revenue available to the government for spending. There should be no concern about this being undemocratic or compromising progressive policy, as politicians would be free to appoint who they like to run the agency. I myself proposed something like this back in 2012.

Lastly, they should revaluate whether PZIRP and fiscal dominance are healthy situations for a government to be in, and the inflation and financial instability that could result, and flesh out a detailed plan on how inflation might be controlled without relying solely on infrequent discretionary legislation passed by politicians. I have recently seen Rohan Grey propose a separate ‘credit policy’, whereby inflation is subdued by controlling the amount of credit that banks are allowed expand. This is a positive direction, although I would argue this is in actuality just reinventing monetary policy (and current interest rate policy serves the same purpose), and combined with PZIRP might just cause the private sector to continually shrink to make way for more government spending, but perhaps that topic is better left for a future article.

I’m Leaving Google — Here’s the Real Deal Behind Google Cloud

Note: this is my first post on Medium — be gentle :). I’m staring at my badge that I’ll be turning in tomorrow, and decided I must share my thoughts before my next gig consumes 100% of my time. These thoughts are my own personal opinions, and do not reflect or represent Google’s opinions or plans.

Let’s start from the end: after almost 6.5 years, I’m leaving what’s IMO the best company in the world to work for. This was my longest stint at any one company. I’m leaving to pursue a high-risk high-reward opportunity with a company that’s disrupting personal finance.

I joined Google Cloud before it was even a platform, and I’m one of the PMs that has spent the longest tenure in Cloud. I’d like to share what I’ve seen over the years and what I expect to see in years to come.

But first, I’d like to tell you why leaving Google is so difficult.

I’ve just realized this photo was taken when I still wore prescription glasses…

What’s so great about Google anyway?

Many people mention great perks and benefits, like free food and four month maternity leaves (unfortunately my 3 boys were born before I’ve joined Google — I only had a couple of days to bond with them!). Not to mention great salaries and a stock that’s rock solid. Young professionals might place a larger weight on these, but they get so much more “free” stuff that’s going to greatly impact their development and future careers. I wish on all my boys to start their careers at Google — because Google provides accelerated learning and development into the most important fields of tech.

1.Heaven for engineers and product managers: the engineering and PM levels at Google are very high. Don’t get me wrong — not everyone is a rockstar. But on average, you can rely on your colleagues to tackle tough problems together, and get hard sh*t done. This is because:

Google has some of the best software development tools and processes in the industry. This is acknowledged by SWEs joining from other tech companies.

There’s no shortage of smarts and experience to learn from. I didn’t have to venture far from my desk to find someone smarter than me. And the advice and experience available in the product org is amazing.

There’s so much focus on personal development. Mentorships, docs from leaders in the field, educational programs and courses. All free and readily available to everyone. Which means with time, people level up.

2. The best culture money can’t buy: the first weeks after I joined two things struck me:

Information is openly available. At TGIF (weekly gatherings with Google founders and execs) I learned about plans and products that were secret to outsiders (later I learned about the leaks that threaten this openness).

People want to help and collaborate — and generally are nice to each other. This isn’t just from my immediate team members, or people that I pinged on chat and immediately responded. This includes internal forums for just about everything: coding, parenting, biking, investing, you name it. And I immediately got the sense Googlers go out of their way to be helpful.

In addition, the culture rewards excellence and innovation, encourages saying “thank you” in public, and promotes great ideas and efforts.

There’s a feeling that people are generally “good”, which why I was completely blindsided (like many others) by the infamous memo of last year. Regardless of where you stand in the conversation, Google treats its employees with unbelievable fairness, especially when compared to other tech firms. Trust me, I’ve been around the block.

3. Innovation and scale all wrapped into one: I crack up whenever I read that some people think Google isn’t innovative anymore. Firstly, the most important field in tech today — Machine Learning — is led by Google, which is several years ahead of its nearest competition. I don’t want to put other companies down — they’re also very innovative. But in the field of AI/ML, nobody comes close. Not in technology and not in the raw numbers of quality engineering talent. Now think of all the things Google applies ML to, like self driving cars, assistant, search, etc. If that’s not innovation — what is?

To find scale, all I need to do is look at the main apps I use throughout my day: Maps, Photos, Chrome, YouTube, Gmail, Search. AFAIK all of these are irreplaceable. Yes, there are alternatives* — but for me, switching means negative impact on my day-to-day.

*I don’t really think there’s an alternative to YouTube. It’s unique. I’ve also spent a short stint working on YouTube data infrastructure, and I can say that the org culture/vibe and the people are pretty amazing.

So no room for improvement? All is perfect in Google-Land? Of course not.

In some areas across Google the execution could’ve been better. Google is willing to bet big on success, and also assumes the risk of big failures. Messaging efforts of past didn’t take off like they should’ve. Google+ was a huge effort that didn’t succeed (but did give birth to the amazing Photos app). There are other examples. But the organization is a learning one, and I’m hopeful that future efforts will integrate these lessons learned.

Another hurdle is due to the (good) fact that there’s a lot of openness to ideas and opinions. Sometimes discussions and debates feel like they’re taking too long, and decisions need to be made sooner. Even if consensus wasn’t achieved or not all opinions were heard. Once we’re done understanding the data, and we’re only left with opinions — time to march on.

Lastly, promotion and perf are areas that finding the right balance is an ongoing process. Every cycle, complaints surface around promo fairness and perf overhead. There’s an entire team working on improving the process, but I feel there’s still work to do. To be fair, it’s tough to find balance in an 80k+ sized company. Google is no longer a startup.

Which brings me to Cloud.

Google Cloud — No Longer a Startup

My first PM task at Google was to launch Monarch — Google’s planet scale monitoring service for Google’s apps and services (Maps, Gmail, etc). Talk about the opposite of “easy early wins”! But with the help of others (see above “Heaven for..”) I managed to successfully launch it, and found my way into the cloud org circa early 2013.

Only back then, it really felt like a startup. We were pressed to find product market fit amidst fierce competitors that had years of head start (AWS) and armies of sales and marketing teams (Azure). And users still had questions of whether or not we were here to stay.

Not surprisingly we’ve found success with customers that were similar to Google. When I first engaged with Snapchat I believe they were less than 10 people, but the scale and automation they were looking for were not unlike what we knew in other parts of Google.

So we’ve made some mistakes. Two meaningful ones to be precise.

Our first — taking too long to recognize the potential of the enterprise. We were led by very smart engineering managers — that held tenures of 10+ years at Google, so that’s what grew their careers and that’s what they were familiar with. Seeing success with Snapchat and the likes, and lacking enough familiarity with the enterprise space, it was easy to focus away from “Large Orgs”. This included insufficient investments in marketing, sales, support, and solutions engineering, resulting in the aforementioned being inferior compared to the competitors’.

The second mistake was chasing the competition. For example, AWS was having great success with EC2 (VMs). And customers were asking for it on GCP. So our native internal way of running things — containers — was to take a backseat for a few years, until a small startup by the name of Docker managed to hype up containers enough to make them relevant. Google took notice, and the rest is history. Another example is App Engine — predating today’s “serverless” hotness by a few years, and arguably a successful business even back then. Neither AWS or Azure had anything like it, but we had to divert too many resources to satisfy customers that were asking for features similar to what our competitors offered at the time.

But all that is in the past. Over the last ~3 years, things have changed substantially. With the current leadership in place (grounded with the right experience), strong focus on enterprise, and marketing/sales/support teams that are correctly leveled and staffed, we’re left with the meat and potatoes: the products.

My friends ask me if I think Google Cloud will catch up to its rivals. Not only do I think so — I’m positive five years down the road it will surpass them. Because today, Cloud is about helping other companies build software like Google does. All those great things about working at Google? Making them available to other companies — that’s the product market fit.

Take Kubernetes as an example. It broke many adoption records and is very successful, and not because of any new concepts that were introduced. Kubernetes is really an externalization of container orchestration that’s been battle hardened inside of Google for many years (called Borg), and built to scale the largest, most distributed web services. And of the three cloud vendors, Google is best positioned to leverage these technologies and innovate first with (much) better offerings.

Security is another area. If I asked you which company had the fewest breaches, or where you feel your information is safest — what would your answer be? And so, it’s no wonder that Google Cloud leads and will continue to lead in this area. Externalizing security features and practices to our customers will prove of significant value — sometimes too valuable to pass for any other reason.

Machine Learning is the third strong pillar. Helping companies utilize advanced ML technologies the way Google does can give businesses an unfair advantage. And so, pretty soon every industry will have to deploy and use it, one way or another.

There are other things, like externalizing what we know about running production at scale (think monitoring, logging and SRE practices), CI/CD, externalizing previously internal services such as Spanner, BigQuery, and BigTable. The list goes on, and the not-yet-realized opportunity is huge.

Fast forward 5 years. What company wouldn’t want to build their service with the same agility, scale, and security that Google does? Scale it to billions of users with minimal disruption and rock solid stability and reliability?

It’s almost midnight, and the post reads more like a love story than someone who’s leaving the company :) I’ll end here and not venture into my next chapter yet — I’ll leave that for my next post. For now I’ll just say that, starting next week my commute is about to get 3x longer ;)

Predictions 2019: Climate, Tech, Trump, Facebook, and…Weed.

If predictions are like baseball, I’m bound to have a bad year in 2019, given how well things went the last time around. And given how my own interests, work life, and physical location have changed of late, I’m not entirely sure what might spring from this particular session at the keyboard.

But as I’ve noted in previous versions of this post (all 15 of them are linked at the bottom), I do these predictions in something of a fugue state — I don’t prepare in advance. I just sit down, stare at a blank page, and start to write.

So Happy New Year, and here we go.

1/ Global warming gets really, really, really real. I don’t know how this isn’t the first thing on everyone’s mind already, with all the historic fires, hurricanes, floods, and other related climate catastrophes of 2018. But nature won’t relent in 2019, and we’ll endure something so devastating, right here in the US, that we won’t be able to ignore it anymore. I’m not happy about making this prediction, but it’ll likely take a super Sandy or a king-sized Katrina to slap some sense into America’s body politic. 2019 will be the year it happens.

2/ Mark Zuckerberg resigns as Chairman of Facebook, and relinquishes his supermajority voting rights. Related, Sheryl Sandberg stays right where she is. I honestly don’t see any other way Facebook pulls out of its nosedive. I’ve written about this at length elsewhere, so I will just summarize: Facebook’s only salvation is through a new system of governance. And I mean that word liberally — new governance of how it manages data across its platform, new governance of how it works with communities, governments, and other key actors across its reach, and most fundamentally, new governance as to how it works as a corporate entity. It all starts with the Board asserting its proper role as the governors of the company. At present, the Board is fundamentally toothless.

3/ Despite a ton of noise and smoke from DC, no significant federal legislation is signed around how data is managed in the United States. I know I predicted just a few posts ago that 2019 will be the year the tech sector has to finally contend with Washington. And it will be…but in the end, nothing definitive will emerge, because we’ll all be utterly distracted by the Trump show (see below). Because of this, unhappily, we’ll end up governed by both GDPR and California’s homespun privacy law, neither of which actually force the kind of change we really need.

4/ The Trump show gets cancelled. Last year, I said Trump would blow up, but not leave. This year, I’m with Fred, Trump’s in his final season. We all love watching a slow motion car wreck, but 2019 is the year most of us realize the car’s careening into a school bus full of our loved ones. Donald Trump, you’re fired.

5/ Cannabis for the win. With Sessions gone and politicians of all stripes looking for an easy win, Congress will pass legislation legalizing cannabis. Huzzah!!!! Just in time, because…

6/ China implodes, the world wobbles. Look, I’m utterly out of my depth here, but something just feels wrong with the whole China picture. Half the world’s experts are warning us that China’s fusion of capitalism and authoritarianism is already taking over the world, and the other half are clinging to the long-held notion that China’s approach to nation building is simply too fragile to withstand democratic capitalism’s demands for transparency. But I think there may be other reasons China’s reach will extend its grasp: It depends on global growth and optimistic debt markets. And both of those things will fail this year, exposing what is a marvelous but unsustainable experiment in managed markets. This is a long way of backing into a related prediction:

7/ 2019 will be a terrible year for financial markets. This is the ultimate conventional wisdom amongst my colleagues in SF and NY, even though I’ve seen plenty of predictions that Wall St. will have a pretty good year. I have no particular insight as to why I feel this way, it’s mainly a gut call: Things have been too good, for too long. It’s time for a serious correction.

8/ At least one major tech IPO is pulled, the rest disappoint as a class. Uber, Lyft, Slack, Pinterest et al are all expected this year. But it won’t be a good year to go public. Some will have no choice, but others may simply resize their businesses to focus on cash flow, so as to find a better window down the road.

9/ New forms of journalistic media flourish. It’s well past time those of us in the media world take responsibility for the shit we make, and start to try significant new approaches to information delivery vehicles. We have been hostages to the toxic business models of engagement for engagement’s sake. We’ll continue to shake that off in various ways this year — with at least one new format taking off explosively. Will it have lasting power? That won’t be clear by year’s end. But the world is ready to embrace the new, and it’s our jobs to invest, invent, support, and experiment with how we inform ourselves through the media. Related, but not exactly the same…

10/A new “social network” emerges by the end of the year. Likely based on messaging and encryption (a la Signal or Confide), the network will have many of the same features as the original Facebook, but will be based on a paid model. There’ll be some clever new angle — there always is — but in the end, it’s a way to manage your social life digitally. There are simply too many pissed off and guilt-ridden social media billionaires with the means to launch such a network — I mean, Insta’s Kevin Systrom, WhatsApp’s Jan and Brian, not to mention the legions of mere multi-millionaires who have bled out of Facebook’s battered body of late.

So that’s it. On a personal note, I’ll be happily busy this year. Since moving to NY this past September, I’ve got several new projects in the works, some still under wraps, some already in process. NewCo and the Shift Forum will continue, but in reconstituted forms. I’ll keep up with my writing as best I can; more likely than not most of it will focus the governance of data and how its effect our national dialog. Thanks, as always, for reading and for your emails, comments, and tweets. I read each of them and am inspired by all. May your 2019 bring fulfillment, peace, and gratitude.