Medium

7 марта 2019

A prisoner in my own body: This is what it’s like to have sleep paralysis.

I went to pull the blankets up and realized I couldn’t move. I tried to scream, but no words came out.

The first time sleep paralysis struck me was in the winter of 2012.

My grandfather had recently died, and I was spending time at my grandmother’s house. After 60 years of marriage, she wasn’t used to being alone or to the sadness an empty home can bring.

Determined to help her in any way I could, I moved into her spare bedroom for a few days. As night came, I tucked her into bed and turned out the light — a task she had done for me on countless occasions growing up. The role reversal saddened me but also gave me an overwhelming urge to protect one of the most important women in my life. I lay down in the next bedroom and listened to her muffled sobs.

I woke up a few hours later, feeling cold. As I went to pull the blankets up around me, I realized I couldn’t move. I began to panic. What was happening to me? Why was my body paralyzed? I tried to lift my arms: Nothing. My head was cemented to the pillow, my body embedded, frozen.

Then the pressure came, pushing against my chest. The more I panicked, the harder it became to breathe. Like something out of a bad horror movie, I tried to scream, but no words came out. Unable to move my eyes, I had no option but to stare upward into the darkness. I couldn’t see anyone else, but for some reason it felt as if I had company. There was a hidden presence and it was tormenting me, refusing to let me go. After what felt like hours but was probably just a few minutes, I was able to move again. Shaking, I switched the bedroom light on and sat upright in bed until morning came.

“Okay, imagine this,” I said to a friend the following evening. “I went to sleep as normal but woke up with Lord Voldemort squatting on my chest.” She laughed. “Umm, Jen, are you sure this wasn’t just a nightmare?” I considered her question. I’d had nightmares before, but this? This was different. This actually happened while I was awake.

“I don’t think so,” I replied. Deep down I was certain that I had been conscious, fully present, just immobilized for what felt like an eternity.

Others I spoke to suggested that perhaps grief was playing a factor. “You’re going through a stressful time, darling,” my mum said, doing her best, as always, to reassure me.

I didn’t want to arrange a doctor’s appointment — it seemed unnecessary to take up valuable National Health Service time (I live in London) — so I turned to Google.

“Wake up, can’t move” I typed into the search field.

Soon enough, I was reading stories from people who knew exactly what I was talking about. “Look at this,” I said to my mother. “Loads of people online have had this, too.” Relieved, I realized we weren’t all unstable or dreaming or joking: We were suffering from sleep paralysis.

Sleep paralysis occurs when the mind wakes up but the body remains asleep. This causes temporary immobility and, in many cases, intense hallucinations. For some people the paralysis lasts seconds, for others several minutes.

Adrian Williams, a professor of sleep medicine at King’s College London and a member of the medical team at the London Sleep Center, says sleep paralysis is a “normal phenomenon that is not dangerous but is distressing.”

As we sleep, our bodies alternate between REM (rapid eye movement) sleep and NREM (non-rapid eye movement) sleep. During the REM stage, our brains are highly active; as a result, this is when our most elaborate dreams occur.

“During dreaming sleep, the body is paralyzed to prevent us from acting out our dreams. Occasionally the body gets confused and the brain wakes yet the paralysis persists,” Williams said.

Episodes are almost always accompanied by a feeling of intense pressure on the chest. Naturally, the inability to breathe rouses feelings of panic and despair. “Because of the paralysis, the only breathing muscle that is working is the diaphragm. There’s often a sense of inadequate breathing because the chest muscles are not working,” Williams said.

Around half of the population has experienced sleep paralysis, he said. Some will notice it frequently, others just once or twice.

Relatively few seek treatment. The London Sleep Center sees only about one sleep paralysis patient every month. “By the time a person goes to see a doctor, the paralysis is usually happening often,” Williams said. “Often patients do not know they’re suffering with sleep paralysis, which is why they come.”

Sleep paralysis is commonly linked with narcolepsy, a rare condition that affects the brain’s ability to regulate the sleep-wake cycle. Williams estimates that two-thirds of narcoleptics also have sleep paralysis.

According to information from the National Health Service, sleep paralysis can be triggered by anxiety, stress and depression — which may explain why my first encounter with the condition came during a time of grief. Those with irregular sleeping patterns are more at risk than others of experiencing the disorder while falling into or waking up from sleep.

“There is no antibiotic to make sleep paralysis go away,” Williams said. “The first thing to do is to focus on making sleep better in a behavioral way.”

Williams said that the condition can be passed through generations but is not gender-related. “I’ve seen three or four families with this problem,” he said.

Many cultures have blamed sleep paralysis on the underworld and mysterious creatures such as the “old hag” and the “devil in the room.” Henry Fuseli’s 1781 painting “The Nightmare” is frequently associated with the disorder: He depicts a sleeping woman sprawled helplessly on a bed as an ogre sits on her chest.

In Thailand, some believe that breathing difficulties at night are caused by the Phi Am spirit — a ghost that sits on your chest and crushes you. Guam has legends of the Taotaomona, a forest vampire spirit that seeks to protect Earth. Those who disrespect the island, the stories say, will be strangled in their sleep.

Williams, who said sleep paralysis occurs more commonly when sleeping on the back, suggests that the problem may by avoided by sleeping on the side. Episodes can be interrupted by touch, he said, so a bed partner may be able to intervene.

When sleep paralysis is happening frequently and efforts to correct it have not been successful, he said, antidepressants are sometimes prescribed, not necessarily because the patient is depressed but in an attempt to suppress REM sleep.

Some people have told me that they are sometimes able to blink themselves out of their paralysis. Others find that slowly moving their fingers and toes helps break the spell.

Since that night in 2012, I have experienced sleep paralysis at least 10 times. Once it struck three times in a single night. It’s terrifying and it’s exhausting.

Now I avoid caffeine before bed and listen to relaxation music while falling asleep. I also keep a sleep journal in which I write down descriptions of episodes. My most recent encounter came over Christmas break. An excerpt:

“3:30 a.m.

“I’m in a room with a man I don’t know. He asks if I want a drink and leaves to make me one when I say yes. But as he leaves, he turns the lights out, plunging me into darkness.

“Instantly I’m uncomfortable, it’s time to go home. . . . but I’m stopped by the other people who are now somehow in the room with me. They emerge from the shadows and begin grabbing me. They’re pulling my fingers, snapping my wrists, they’re tugging my hair until it falls out in patches onto the carpet below. I’m frozen, unable to escape. A prisoner.

“My attackers disappear and the lights are back on, but I’m stuck to the floor of this unfamiliar room. I’m lying on my back unable to scream. I’m trying to shout but nothing comes out. I begin smacking my bare arm against a wooden desk, desperate to draw attention to myself.

“Bang bang bang. My arm turns purple, it bleeds. I smash it against the desk until there’s a hole in my skin and I can see the bone underneath. Nobody hears me and nobody comes.”

It’s over just as quickly as it started. I’m awake and I’m safe at home. My fingers aren’t broken and there is no one else in the room. I check my arm. It’s cold but not bloody or bruised. Sleep paralysis strikes again.

3 марта 2019

Facebook Can’t Be Fixed.

Facebook’s fundamental problem is not foreign interference, spam bots, trolls, or fame mongers. It’s the company’s core business model, and abandoning it is not an option.

Mark Zuckerberg has announced his annual “personal challenge,” which in the past has ranged from eating meat he personally kills to learning Mandarin.

This year, his personal challenge isn’t personal at all. It’s all business: He plans to fix Facebook.

In his short but impactful post, Zuckerberg notes that when he started doing personal challenges in 2009, Facebook did not have “a sustainable business model,” so his first pledge was to wear a tie all year, so as to focus himself on finding that model.

He sure as hell did find that model: data-driven audience-based advertising, but more on that in a minute. In his post, Zuckerberg notes that 2018 feels “a lot like that first year,” adding “Facebook has a lot of work to do — whether it’s protecting our community from abuse and hate, defending against interference by nation states, or making sure that time spent on Facebook is time well spent….My personal challenge for 2018 is to focus on fixing these important issues.”

The post is worthy of a doctoral dissertation. I’ve read it over and over, and would love, at some point, to break it down paragraph by paragraph. Maybe I’ll get to that someday, but first I want to emphatically state something it seems no one else is saying (at least not in mainstream press coverage of the post):

You cannot fix Facebook without completely gutting its advertising-driven business model.

And because he is required by Wall Street to put his shareholders above all else, there’s no way in hell Zuckerberg will do that.

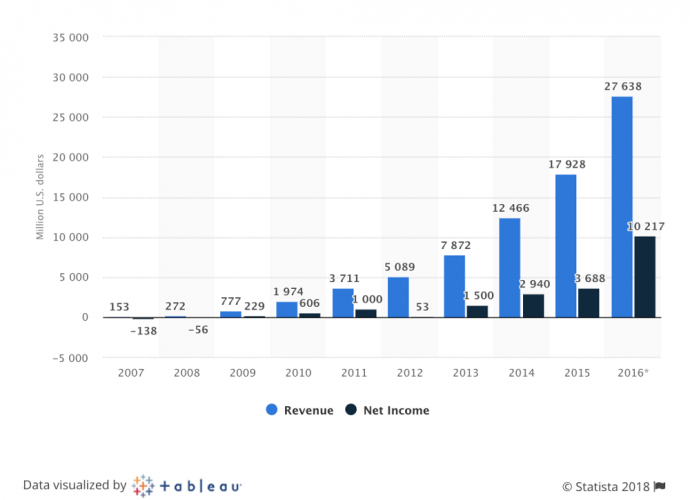

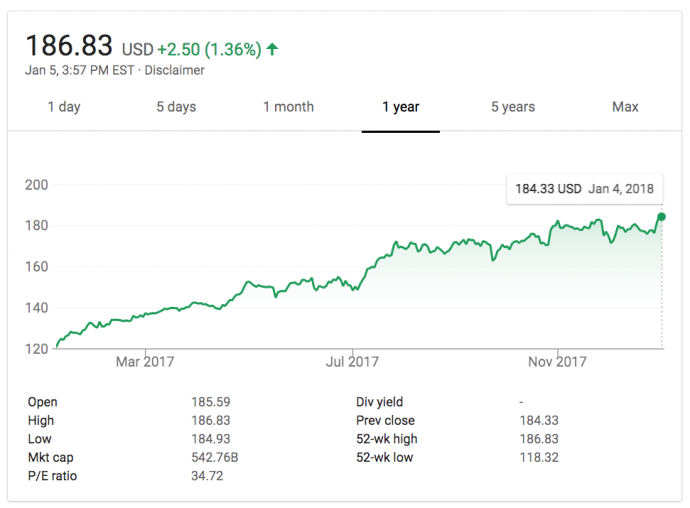

Put another way, Facebook has gotten too big to pivot to a new, more “sustainable” business model. The company is on track to earn at least $16 billion in profits in 2017. Wherever the number lands (earnings for the year come out later this month), it’s at least 50 percent growth on the year before. As a stock, Facebook is breaking out in a massive way — it’s priced at roughly 36 times earnings — a healthy premium to the S&P’s average of around 25. Facebook’s financials from its first year through 2016 are in the opening image above. Here’s the stock price in 2017:

The stock is trading at $186 or so today; it began the year at roughly $120. As we all know, a stock price is the market’s estimate of future earnings. If Zuckerberg decides to really “fix” Facebook, well, that stock price will nosedive. And that will lead angry shareholders to sue the stuffing out of the company, and likely demand the CEO’s head on a pike.

If you’ve read “Lost Context,” you’ve already been exposed to my thinking on why the only way to “fix” Facebook is to utterly rethink its advertising model. It’s this model which has created nearly all the toxic externalities Zuckerberg is worried about: It’s the honeypot which drives the economics of spambots and fake news, it’s the at-scale algorithmic enabler which attracts information warriors from competing nation states, and it’s the reason the platform has become a dopamine-driven engagement trap where time is often not well spent.

To put it in Clintonese: It’s the advertising model, stupid.

We love to think our corporate heroes are somehow super human, capable of understanding what’s otherwise incomprehensible to mere mortals like the rest of us. But Facebook is simply too large an ecosystem for one person to fix. And anyway, his hands are tied from doing so. So instead, he’s doing what people (especially engineers) always do when the problem is so existential they can’t wrap their minds around it: He’s redefining the problem and breaking it into constituent parts.

Here are two scenarios for what might come of Zuckerberg’s 2018 quest:

Facebook identifies a set of issues (Abuse and Hate, Interference by Nation States, Time Well Spent) and convenes working groups with panels of experts and pundits. The press is duly impressed, the lobbyists make sure Congress is kept in the loop, and in the end, they come up with well-intentioned but feckless point solutions which are implemented with little to no effect. The stock keeps climbing.

Zuckerberg does the equivalent of dropping corporate acid and realizes the only way to fix Facebook is to make a massive, systemic change. He orders his team to redesign the entire Facebook product suite around a new True North: No longer will his company be driven by engagement and data collection, but rather by whether or not individual users report that they are happier after using the service. This leads to a massive rethink of the product and advertising platform, which after much debate shift from an audience model (deep data, specific to each individual) to a contextual model (not buying people, but buying the context in which those people are engaging). And given that most of an individual’s context on Facebook has to do with engaging with friends and family, well, ad inventory plunges. Maybe, just maybe, Facebook decides to charge a subscription fee, say, $10 a person per year. That alone could arguably bring in $20+ billion annually, but…let’s remember, I’m describing an acid trip.

Which do you think will happen?

Yeah, me too. If Zuckerberg picks #2, his business would shrink by tens of billions of dollars. It’d still be an awesome business, and he’d probably be a lock for Man of the Year. But it’d get his assed sued into oblivion by angry shareholders.

Then again….Zuckerberg is one of several tech founders who hold super majority shares that give him absolute control over the future of his company. The stated reason for this structure, popularized by Google founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page, was to ensure that the capitalistic vagaries of Wall St. don’t force visionary companies to hew to corporatist rationale as they mature. (Page and Brin actually name-checked the New York Times as their inspiration.)

Will Zuck drop acid? Let’s just say this: He certainly could.

FacebookAdvertisingMediaTechFinance

The “Other Side” Is Not Dumb

There’s a fun game I like to play in a group of trusted friends called “Controversial Opinion.” The rules are simple: Don’t talk about what was shared during Controversial Opinion afterward and you aren’t allowed to “argue” — only to ask questions about why that person feels that way. Opinions can range from “I think James Bond movies are overrated” to “I think Donald Trump would make an excellent president.”

Usually, someone responds to an opinion with, “Oh my god! I had no idea you were one of those people!” Which is really another way of saying “I thought you were on my team!”

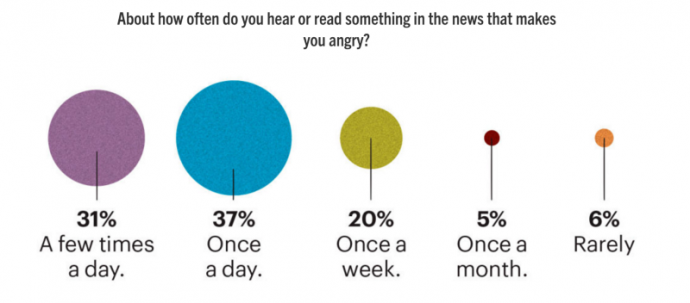

In psychology, the idea that everyone is like us is called the “false-consensus bias.” This bias often manifests itself when we see TV ratings (“Who the hell are all these people that watch NCIS?”) or in politics (“Everyone I know is for stricter gun control! Who are these backwards rubes that disagree?!”) or polls (“Who are these people voting for Ben Carson?”).

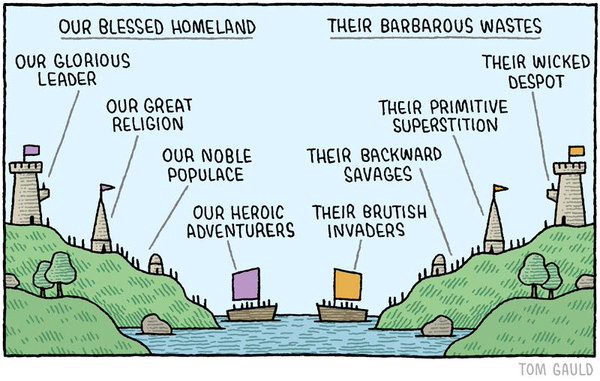

Online it means we can be blindsided by the opinions of our friends or, more broadly, America. Over time, this morphs into a subconscious belief that we and our friends are the sane ones and that there’s a crazy “Other Side” that must be laughed at — an Other Side that just doesn’t “get it,” and is clearly not as intelligent as “us.” But this holier-than-thou social media behavior is counterproductive, it’s self-aggrandizement at the cost of actual nuanced discourse and if we want to consider online discourse productive, we need to move past this.

What is emerging is the worst kind of echo chamber, one where those inside are increasingly convinced that everyone shares their world view, that their ranks are growing when they aren’t. It’s like clockwork: an event happens and then your social media circle is shocked when a non-social media peer group public reacts to news in an unexpected way. They then mock the Other Side for being “out of touch” or “dumb.”

Fredrik deBoer, one of my favorite writers around, touched on this in his Essay “Getting Past the Coalition of the Cool.” He writes:

[The Internet] encourages people to collapse any distinction between their work life, their social life, and their political life. “Hey, that person who tweets about the TV shows I like also dislikes injustice,” which over time becomes “I can identify an ally by the TV shows they like.” The fact that you can mine a Rihanna video for political content becomes, in that vague internety way, the sense that people who don’t see political content in Rihanna’s music aren’t on your side.

When someone communicates that they are not “on our side” our first reaction is to run away or dismiss them as stupid. To be sure, there are hateful, racist, people not worthy of the small amount of electricity it takes just one of your synapses to fire. I’m instead referencing those who actually believe in an opposing viewpoint of a complicated issue, and do so for genuine, considered reasons. Or at least, for reasons just as good as yours.

This is not a “political correctness” issue. It’s a fundamental rejection of the possibility to consider that the people who don’t feel the same way you do might be right. It’s a preference to see the Other Side as a cardboard cut out, and not the complicated individual human beings that they actually are.

What happens instead of genuine intellectual curiosity is the sharing of Slate or Daily Kos or Fox News or Red State links. Sites that exist almost solely to produce content to be shared so friends can pat each other on the back and mock the Other Side. Look at the Other Side! So dumb and unable to see this the way I do!

Sharing links that mock a caricature of the Other Side isn’t signaling that we’re somehow more informed. It signals that we’d rather be smug assholes than consider alternative views. It signals that we’d much rather show our friends that we’re like them, than try to understand those who are not.

It’s impossible to consider yourself a curious person and participate in social media in this way. We cannot consider ourselves “empathetic” only to turn around and belittle those who don’t agree with us.

On Twitter and Facebook this means we prioritize by sharing stuff that will garner approval of our peers over stuff that’s actually, you know, true. We share stuff that ignores wider realities, selectively shares information, or is just an outright falsehood. The misinformation is so rampant that the Washington Post stopped publishing its internet fact-checking column because people didn’t seem to care if stuff was true.

Where debunking an Internet fake once involved some research, it’s now often as simple as clicking around for an “about” or “disclaimer” page. And where a willingness to believe hoaxes once seemed to come from a place of honest ignorance or misunderstanding, that’s frequently no longer the case. Headlines like “Casey Anthony found dismembered in truck” go viral via old-fashioned schadenfreude — even hate.

…

Institutional distrust is so high right now, and cognitive bias so strong always, that the people who fall for hoax news stories are frequently only interested in consuming information that conforms with their views — even when it’s demonstrably fake.

The solution, as deBoer says, “You have to be willing to sacrifice your carefully curated social performance and be willing to work with people who are not like you.” In other words you have to recognize that the Other Side is made of actual people.

But I’d like to go a step further. We should all enter every issue with the very real possibility that we might be wrong this time.

Isn’t it possible that you, reader of Medium and Twitter power user, like me, suffer from this from time to time? Isn’t it possible that we’re not right about everything? That those who live in places not where you live, watch shows that you don’t watch, and read books that you don’t read, have opinions and belief systems just as valid as yours? That maybe you don’t see the entire picture?

Think political correctness has gotten out of control? Follow the many great social activists on Twitter. Think America’s stance on guns is puzzling? Read the stories of the 31% of Americans that own a firearm. This is not to say the Other Side is “right” but that they likely have real reasons to feel that way. And only after understanding those reasons can a real discussion take place.

As any debate club veteran knows, if you can’t make your opponent’s point for them, you don’t truly grasp the issue. We can bemoan political gridlock and a divisive media all we want. But we won’t truly progress as individuals until we make an honest effort to understand those that are not like us. And you won’t convince anyone to feel the way you do if you don’t respect their position and opinions.

A dare for the next time you’re in discussion with someone you disagree with: Don’t try to “win.” Don’t try to “convince” anyone of your viewpoint. Don’t score points by mocking them to your peers. Instead try to “lose.” Hear them out. Ask them to convince you and mean it. No one is going to tell your environmentalist friends that you merely asked follow up questions after your brother made his pro-fracking case.

Or, the next time you feel compelled to share a link on social media about current events, ask yourself why you are doing it. Is it because that link brings to light information you hadn’t considered? Or does it confirm your world view, reminding your circle of intellectual teammates that you’re not on the Other Side?

I implore you to seek out your opposite. When you hear someone cite “facts” that don’t support your viewpoint don’t think “that can’t be true!” Instead consider, “Hm, maybe that person is right? I should look into this.”

Because refusing to truly understand those who disagree with you is intellectual laziness and worse, is usually worse than what you’re accusing the Other Side of doing.

[Thanks for reading! If you liked this, you’d love “The Discourse,” my newsletter about the intersection of tech, media, and politics. Subscribe here. Sent every other Thursday.]